31 Oct 2021 - Kobi

This article describes the role and sources of randomness in cryptographic protocols

The post is co-authored with Tom.

Background

Randomness is ubiquitous across the cryptography underpinning blockchain infrastructures — in the Merkle trees securing state, in the random-selection mechanism in proof of work, in the selection of committees in proof of stake, and in the zero knowledge proofs underpinning both scaling and privacy.

Hash functions are the most important source of randomness in these protocols.

What’s a Hash Function?

A hash function takes in a ‘message’ (this could be any data — the state of a blockchain, the contents of a transaction, etc) and ‘spits out’ a digest of a fixed length, in some predefined ‘space’ of numbers. This could be all numbers up to \(2^{256}\), or it could be elements of a prime field (common in zero knowledge proofs), or even sometimes elliptic curve points, which are numbers of a different kind.

The point is, the ‘magnitude’ of the output given the input should be completely unpredictable, until the hash is actually computed.

Hashes are typically seen in two settings:

As a short ‘unique fingerprint’ on data (typically the ‘state’ of the blockchain, or the contents of a transaction), and

A way of replacing questions that should be supplied by the verifier in certain ‘interactive protocols’. This is a common feature of zero knowledge proofs. The security of interactive protocols depends on a sequence of questions and answers between the ‘verifier’ and the ‘prover’. Hashes can be used to remove the need for a direct back-and-forth dialogue between the prover (usually the spender of money) and the verifier (the blockchain nodes checking all transactions are correct)

Property #1 for Hashes: Randomness

A core property of hash functions is therefore they scramble input data in a seemingly random fashion. When new hash functions are proposed, they must be subjected to rigorous statistical tests to satisfy the cryptography community that they do indeed exhibit their claimed randomness. Any failure to do so would produce features that expose protocols relying on them to potential attack.

This randomness is useful in many contexts.

Pseudorandom Function Families (PRFs) are functions that, similar to hash functions, map a message to an output, but additionally have a key as an input. PRFs can be built from these random-looking hashes, and, for example, can be used to build message authentication codes, to protect message authenticity and integrity. These hashes can also help when converting interactive proofs to non-interactive. If during the interactive proof a verifier sends uniformly random elements to the prover as challenges, the Fiat-Shamir heuristic can use a hash to replace the interactive random challenge with a hash of the proving process messages so far, as this should produce a sufficient random element for this purpose.

Property #2 for Hashes: Collision Resistance

Additionally, we want it to be the following:

Collision-resistant - hard to find two different messages that produce the same result

Pre-image resistant - given an output, hard to find an input that produces it

Second pre-image resistant - given an input and output, hard to find another input that produces the same output

The desire for collision-resistance is direct - if we digest two different messages into the same hash, we can’t distinguish them anymore. Therefore, we want the short hash digest to be as unique as possible for different messages, in the sense that we can’t maliciously craft messages that have the same hash. As a rule of thumb, collision resistance is usually easier to attack than pre-image resistance. This is because in collision resistance you have the freedom to choose any two inputs, where in both variants of pre-image resistance you are restricted to a specific output. Birthday attacks immediately reduce the complexity of finding a collision to a square root of the amount of possible outputs. Generally, when a collision is found, it’s a strong signal hash function should be phased out, as it signals worse attacks may happen.

Another common place where it appears is some signature schemes: in Schnorr signatures we require a “hash to field” and in BLS signatures we require a “hash to group”. In both cases, this hash provides us with a unique element from the target set that is unrelated to other results of the hash. For example, we don’t want it to be the case that if you call the hash function \(H\) on \(m_1\) and \(m_2\), then you can also somehow deduce \(H(m_3)\).

Provable Security and the “Standard Model”

Hashes, then, sound super useful! What’s the problem?

While useful for protocol designers, introducing hash functions to protocols makes life hard for cryptographers, when they approach proving security for the protocols. Cryptographers like to work with reductions - you formulate a security property for your protocol, and show that if that security property is broken by an adversary, then it implies that we also solved an unsolvable problem, an assumption.

Proving security of protocols using computational hardness assumptions is considered working within the Standard Model. This means that you assume some problems are hard, and try to prove that your protocol’s security properties can be explained to be as hard as this problem. One such problem that is widely known is the Discrete Logarithm problem in a group: given \(g\) and \(h\), find \(x\) such that \(g^x = h\). If someone wants to break your protocol’s security properties, and you prove that in order to break it you would have to find a Discrete Logarithm, then you’re in a really good shape.

A concrete example is the case of ElGamal encryption, where we have the IND-CPA property that roughly states that even if you know a ciphertexts is an encryption of one of a set of plaintexts you’ve chosen, you will not be able to know which of the plaintexts was chosen. The assumption that is solved if that property is broken is DDH - Decisional Diffie Hellman, that states that \((g^x, g^y, g^{xy})\) is indistinguishable from \((g^x, g^y, g^z)\), given random \(x,y,z\) and a group generator \(g\).

Hashes throw a wrench into that and constrain the ability of cryptographers to make such reductions, and without an alternative modeling of the protocol, we would be left with “we’ve tried to break this protocol for some time and couldn’t”, which feels unsatisfactory.

Random Oracles to the Rescue

Random oracles can solve this.

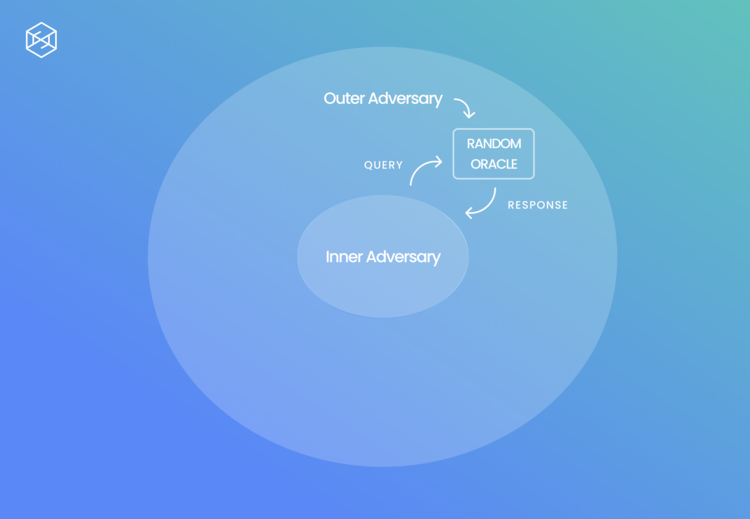

They provide a way to do a security-reduction proof, to gain confidence in the security of the protocol. When working within the Random Oracle Model, we replace each hash functions with an idealized Random Oracle:

When a query is made on a new message, a random response from the target set is returned, chosen uniformly from it.

When a query on a message that has been queried on before, the same response as before is returned.

“Programmable” Random Oracles

This introduces the concept of programmable random oracles, in which we allow some of the participants to program it — return values of its choosing, as long as they appear random to the receiver. It may sounds a bit weird, since the functions we would use in reality don’t have that feature. Given that it allows cryptographers provide positive results on the security of some protocols and that the consumer of oracle doesn’t see the difference, as they still see random values, it seems like a reasonable trade-off to make.

Specifically, we can allow an adversary that wants to break an assumption, let’s say DDH, to simulate the environment of another adversary that claims they know to break a security property of the protocol.

By programming the random oracle, we can use the responses from the adversary whose environment to then break the assumption.

There are a few other different variants, providing different levels of confidence - for example, non-programmable random oracles.

It’s not all Roses

Alright, this sounds really powerful. What’s the catch? The catch is that random oracles don’t really exist. Good hashes only approximately behave like them.

Take one of the most famous hashes — SHA-256. Try inputting a few numbers, SHA(1), SHA(2), etc. Run a few statistical tests to see in which ‘regions’ of the number grid \(2^{256}\) looks random.

But true random functions don’t exist, almost by definition — a function is algorithmic, deterministic. Even worse, since random oracles don’t really exist, there are pathological examples where a scheme is proven to be secure in the random oracle model but is insecure when instantiated with any hash function.

So is this at all useful? It gives a bit of confidence and it helps catching bad protocol design mistakes in other parts of the protocol. The intuition is that if your hash function behaves like a random oracle, then the proof somewhat applies to it. If it doesn’t, then the proof doesn’t even patter. It’s also sometimes the best we can get for some protocols, so it’s much better than nothing.

You may also wonder - what are good instantiations of random oracles? When the source and target spaces are just sequences of bytes, they can more easily be built directly from known hash functions, like SHA256. When we’re talking about prime fields and elliptic curve groups it’s harder and there are many pitfalls on the way.

What’s Next?

If you’re curious to see how programmable random oracles can be used to prove security for the famous BLS signature scheme, read the appendix!

Lastly, if you want to try to break a protocol which uses a subtly bad instantiation of a random oracle, check out the first puzzle of zkhack :)

Appendix

BLS security proof

Let’s look at a shortened version of a concrete example, BLS signatures (if you need some background on BLS signatures, I recommend reading this:

Assumption - co-CDH: Given \(g_1^a \in \mathbb{G}_1\), \(g_2^a \in \mathbb{G}_2\) and \(h \in \mathbb{G}_2\), computing \(h^a \in \mathbb{G}_2\) is hard. We are given \(g,g^a,h\) as a challenge.

Security property - Existential Unforgability, roughly stating that given a public key \(pk\), even if you see a bunch of signatures on different messages, you will not be able to forge a signature on another message without access to the secret key.

Proof method sketch:

We build an adversary \(A\) that breaks co-CDH.

The adversary \(F\) who claims they break Existential Unforgability is given a public key \(pk=g^a \in \mathbb{G}_1\), the same one that is received in the challenge where both \(A\) and \(F\) don’t know \(a\), and makes a few random oracle queries while they’re still in the first phase of getting signatures on different messages. They also make signature queries. We know that they will make more random oracle queries than signature queries, since they have a phase where they request signatures, which implies both a random oracle query and a signaturequery , and a phase where they forge a signature, which means they query the random oracle but don’t request a signature.

We guess beforehand an index of a message where \(F\) queries the random oracle but does not request a signature. This would also be the message for which \(F\) forges a signature.

In those queries where both a random oracle is queries and a signature is requested, we have to provide answers that would pass the BLS verification check \(e(pk, H(m)) = e(g_1, \sigma)\) and also look random. We choose a random \(r\), and compute \(H(m) = g_2^r, \sigma = (g_2^a)^r\), Note that we can do that without knowing \(a\) and this still passes the verification check.

In the query where \(F\) only queries the random oracle, we embed the rest of the challenge that we got: \(H(m) = g_2^r \cdot h\). Note that for this case we couldn’t compute \(\sigma\) if we were requested - since we don’t know the entire exponent, it’s not only \(r\) anymore. Also note that this still appears random since \(h^r\) appears random.

Since \(F\) knows to forge a signature \(\sigma\) that satisfies \(e(pk,H(m)) = e(g_1, \sigma) \Rightarrow e(g_1^a, g_2^r \cdot h) = e(g_q, \sigma)\), we have that \(\sigma = (g_2^r \cdot h)^a\). Taking \(\frac{\sigma}{(g_2^a)^r}\), we get \(h^a\) as desired!

Broken hash-to-curve

Recall that we’re looking for a hash that takes a mesage and gives a group element. One particular example I’ve seen in the wild which is broken is doing it in two steps: hash to field \(H(m)\) and then multiply by the generator \(g_2^{H(m)}\). This is broken since given a signature, being \(g_2^{H(m)x}\), where \(x\) is the secret key, we can transform it into a signature for \(m’\) without knowing \(x\), by doing \((g_2^{H(m)x})^{H(m)^{-1}H(m')} = g_2^{H(m')x}\).