16 Jul 2018 - Kobi

Creating fake zkSNARK proofs

As you may know, zkSNARKs are a way to create Zero-Knowledge Proofs. Specifically, succinct and non-interactive ones.

Explaining what they are exactly is a bit too much for this post, so I refer you to the following:

- How zkSNARKs are constructed in — by the Zcash team.

- Trustless Computing on Private Data — blog post by QED‐it’s lead cryptographer Daniel Benarroch and Prof. Aviv Zohar.

- Prove-it, Blockchain-it: ZKP in Action — a video of a meetup explaining ZKPs and how to create one for Sudoku.

- The Incredible Machine — blog post by QED‐it’s Chief Scientist Prof. Aviv Zohar, explaining trusted setup.

- The Hunting of the SNARK — a series of riddles to experiment with ZKPs.

In QED-it we use zkSNARKs, among other tools, to create Zero-Knowledge Blockchains for the enterprise.

The production deployment of zkSNARKs that is most known is probably Zcash — a cryptocurrency with unlinkable transactions and hidden amounts. Zcash, and some others utilizing zkSNARKs, are based on a construction called Pinnochio, although more specifically BCTV14a.

This is a marvelous technology, and as you might suspect, nothing is for free! There’s a notable downside to this construction — the “trusted setup”.

Trusted Setup

The setup is a process where the CRS (Common Reference String) is generated, or more publicly known as the pair of proving and verification keys. These “keys” are used by the prover and verifer to generate and verify proofs for a specific problem (or constraint system), respectively.

In this process, there are random elements which are sampled and must be kept secret — if the prover knows them, they will be able to create proofs which are verified successfully, without using an actual solution to the problem during the proving process. In other words, to forge proofs and break soundness. This randomness is also known as “toxic waste”.

There are ways to avoid this worry and not put trust in a single entity. For public circuits, these usually involve a Multi-Party Computation — a process in which multiple players donate their own randomness, which they destroy afterwards. The interesting fact is that it’s enough that one player is honest and destroys their randomness for the whole process to be secure.

Some notable examples of using MPCs to do trusted setup are again, by Zcash:

You might notice this “Tau” that popped up there…

Not to insult any random element — Tau is very important to be kept secret. With Tau known to the prover — it’s very easy to forge a proof!

Creating a proof

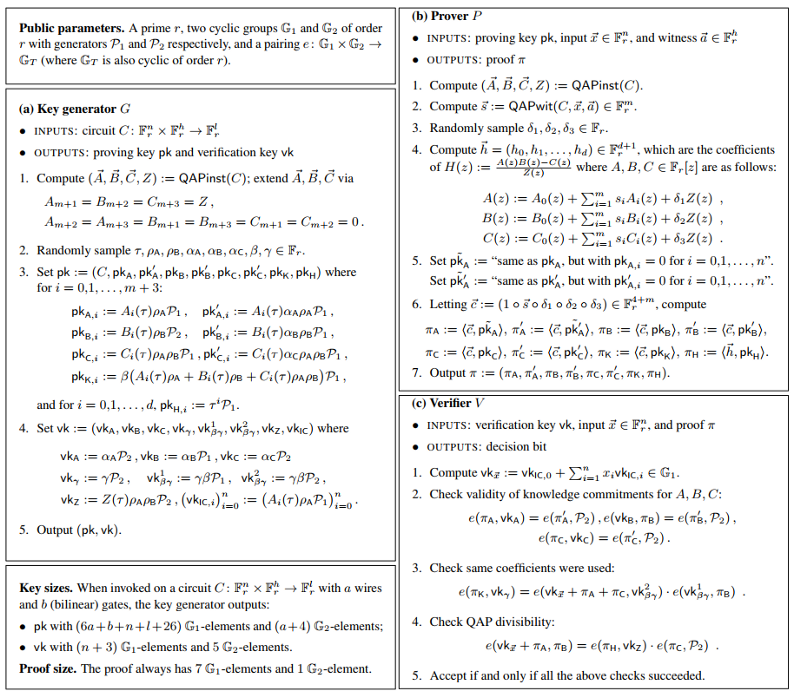

Let’s take a quick look at the construction presented in BCTV14a:

It’s math-heavy, so let’s cherry-pick bits of details relevant to this post:

- Tau is a point in a finite field sampled at random, part of the “toxic waste”, during the setup process.

- The prover, during the proving process, calculates some polynomials — A(z),B(z) and C(z), which are derived from the constraint system and the public and private inputs to the solution. Essentially, these polynomials represent constraints of the form “ab=c”, or equivalently “ab-c=0”.

- The prover also calculates H(z) = (A(z)B(z)-C(z))/Z(z), where Z(z) is a publicly known polynomial which zeros at the points representing the constraint system. Take note that since A,B and C take the inputs of the prover into account, H can only be calculated when the numerator also zeros at the same points — attesting to the fact the prover actually knows a solution to the problem, that which yields A*B-C = 0.

The important part happens now — the prover, while not knowing Tau, can calculate “in-the-exponent” H(z) evaluated at Tau — \(H(\tau)\)!

Why do we do that? Since by evaluating at the random point Tau, the prover shows with high probability that the equation H=(A*B-C)/Z holds for all z. From a different perspective on the same matter, without knowing Tau, the prover, with high probability, will not be able to produce a polynomial which receives the exact same value at that point.

How can we technically do that? By the fact that part of the setup process generated elements containing all the relevant powers of Tau, hidden in the exponent, given as \(pk_{H_i}\). If we have the coefficients of H, we can combine these and create \(H(\tau)\).

More specifically:

| \(H(z) = \sum{h_i \cdot z^i }\) |

|---|

| Calculated H(z) by the prover |

| \({pk}_{H_i} = \tau^i \cdot G_i\) |

|---|

| Taken from the proving key, calculated in the setup process |

| \(\sum{h_i \cdot {pk}_{H_i} } = \sum{h_i \cdot \tau^i \cdot G_1} = H(\tau) \cdot G_1\) |

|---|

| Evaluating \(H(\tau)\) “in-the-exponent” |

The verifier, upon receiving the proof, can check, again in-the-exponent, that the prover indeed provided coefficients for H which satisfy the relation H=(A*B-C)/Z, which can only be done if the prover actually knew a solution.

Forging a proof

Now let’s have some fun… What happens if Tau is known? If, by some reason, it was exposed during the setup process and is known to a malicious prover?

Apparently, it’s very easy to forge a proof — since the equality check for H=(A*B-C)/Z is done is at the specific point Tau, we can use our knowledge of Tau to create a polynomial which satisfies exactly that! That is, create a constant polynomial H(z), which just returns \((A(\tau) \cdot B(\tau)-C(\tau))/Z(\tau)\) all the time.

The verifier’s check will pass, and none’s the wiser!

Sounds hard…

Not at all — you’re more than welcome to check this proof-of-concept code, based on Howard Wu’s libsnark-tutorial, and see for yourself the changes made to the code:

- The program sets up a circuit for bit-decomposition — this is an example, and it could have been any circuit.

- The setup process maliciously saves Tau to disk.

- The prover loads Tau from disk, and uses wrong inputs to the proof. The prover, knowing Tau, generates the constant polynomial, disregarding the inputs.

- The verifier then verifies the proof successfully — bamboozled!

Conclusions

I hope this post provided some insight into what is this “toxic waste” that everyone has been talking about regarding zkSNARKs, and why having it exposed leads to an easily executable attack.